Pocketblog has gone back to basics. This is part of an extended management course.

Change is a never-ending part of organisational life, and managing it effectively is one of the principal challenges for managers. So you need to understand the process, so that you can support effective change in the people who make up your organisation.

This was a topic addressed by one of the twentieth century’s leading thinkers in workplace psychology (and a regular feature of the Management Pocketblog – see below); Kurt Lewin. Among his many contributions to our understanding of organisational life is a three-part model of change.

Forces for Change

Lewin regarded us as subject to a range of forces within our environment, which he divided into:

- Driving Forces, which promote change, and

- Restraining Forces, which hinder it, consisting of our inner resistance to change and our desire to conform to what we perceive to be the established social norms.

Three Phases of Change

1. Unfreezing

Lewin identified the first phase of change as unfreezing established patterns of behaviour and group structures. We do this by challenging existing attitudes, beliefs and values, and then offering alternatives. This allows people to start to relax from their restraining forces; preparing them for change.

2. Changing

The second phase is changing, in which we lead people through the transition to a new state. This is a time of uncertainty and confusion, as people struggle to build a clear understanding of the new thinking and practices that will replace the old. The range of different responses you will encounter means that good leadership is essential. Without it, people will follow whatever weak leadership they can find. A great danger is people’s susceptibility to gossip and rumour during times of change.

3. Freezing

Eventually, a new understanding emerges. Lewin’s third phase is freezing (sometimes refreezing) these new ways of being into place, to establish a new prevailing mind-set. During this phase, people adapt to the changed reality and look for ways to capitalise on the new opportunities it offers. Alternatively, they might instead make a decision to opt-out from the change and move on.

Subsequent Interpretations

When Lewin described this model, he was clear that the phases represent parts of a continuous journey; not discrete processes. However, not everyone understood this – or even took the time to read Lewin’s own writing. The model became neglected largely because his use of the term ‘phases’ led to false interpretations that he was referring to static stages.

However, we might equally argue that his thinking is in rude health. In his excellent 1980 book, ‘Managing Transitions: Making the Most of Change’, William Bridges put forward a similar three stage model of changes, or transitions:

- Letting go

- Neutral zone

- New beginning

Bridges’ books are best sellers that give readers much practical advice on how to support people through each of the three stages of their transition.

Whether in the original form proposed by Lewin, or in the more modern form presented by Bridges, the three phases model is immensely valuable. It focuses us on how to move people through change. As both the first systematic work on organisational change and as a starting point for designing a change process, an understanding of this model is vital for any manager who is working in the arena of change.

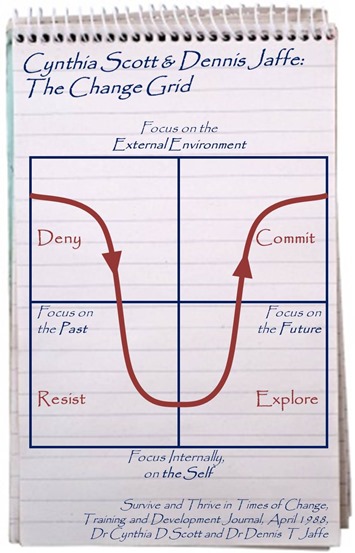

Next week, we will look at a complementary model of how people respond to imposed change, developed by Cynthia Scott and Dennis Jaffe.

- The Managing Change Pocketbook

- The Handling Resistance Pocketbook

- Frontiers in group dynamics: Concept, method and reality in social science; social equilibria and social change, Kurt Lewin, in Human Relations (1947).

- Managing Transitions,

William Bridges, Nicholas Brealey Publishing, Rev Ed 2003

Three Management Pocketblogs about Kurt Lewin

- The World belongs to Unreasonable People

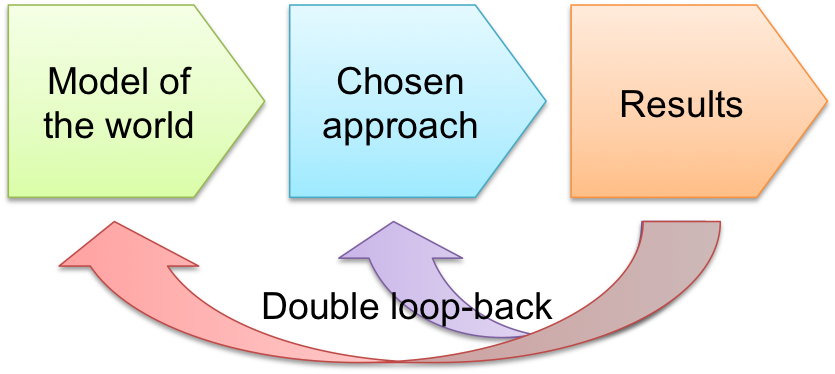

The CECA Loop - Elastic Management

Kurt Lewin’s Force-field Analysis - Predicting Behaviour

Lewin’s equation for predicting behaviour