Pocketblog has gone back to basics. This is part of an extended management course.

If you want to understand your value chain, with the intention of improving it, perhaps, you need first to be able to visualise it. You can do this by preparing a ‘process map’.

The purpose of this blog is to introduce you to two widely used methodologies for mapping out and illustrating processes.

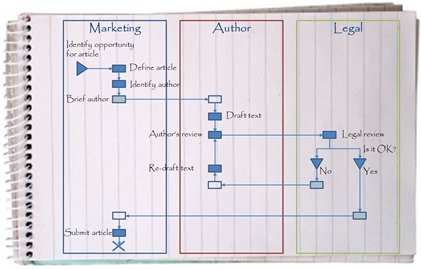

The Role-Activity Diagram (RAD)

Role activity diagrams are based on three concepts:

- The roles that people, teams or departments play in the process

- The activities that players fulfil during the process

- The interaction between one activity and another

The RAD below illustrates the process for a manager writing a marketing article on behalf of their organisation, for a trade journal. You can click on the image to see a larger version.

The symbols on the chart are explained below.

Roles include individuals, positions or posts, jobs, teams, departments, companies, organisations like regulators or unions, or a class of stakeholder like customers or residents. Activities tend to create change, like making, checking, briefing or selling. The interactions can be anything that involves two or more roles, such as moving materials or information, allocating or delegating work, authorising or agreeing a decision, or reporting status.

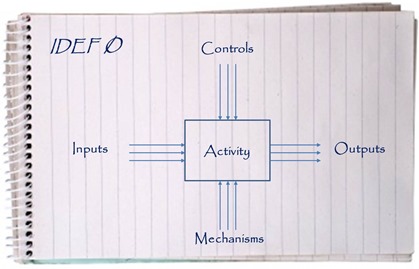

The IDEF Method

IDEF stands for ‘Integrated definition method for function modelling’. It presents processes as flow diagrams with activities as boxes, using a standard set of directions. The process flows from left to right with:

Inputs

… shown coming from the left

These can be materials, ideas, information or services that input into the process

Outputs

… shown coming out from the right

These can be information, services or products that are produced by the process

Controls

… shown applied from the top

These are the decisions and information that control the process

Mechanisms

… shown applied from below

This can be a person, team, system, service or supplier that performs or assists in the process

Strictly speaking, this is one of a family of IDEF modelling tools; IDEF0. You can learn more about IDEF1, IDEF1X, IDEF3, IDEF4 and IDEF5 at the IDEF website. These (and other) IDEF tools form a large family (Wikipedia lists 15) of systems and software modelling languages.

IDEF0, however, is very suitable of modelling organisational processes and has the merit that it can translate well into setting out a functional requirement for a system development.