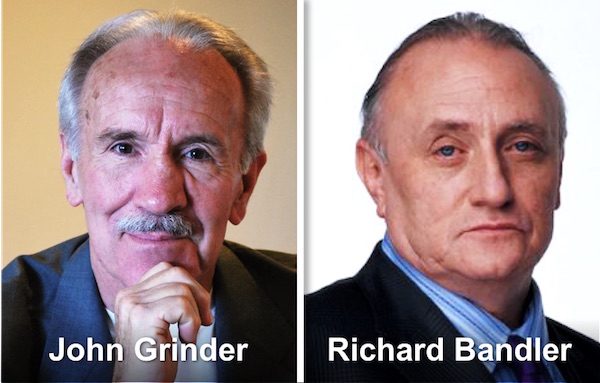

Kenneth Thomas

Kenneth Thomas gained his BA from Pomona College in 1968, quickly becoming a research Fellow at Harvard for a year. He then started a PhD in Administrative Sciences at Purdue University, whilst holding a junior teaching position at University of California, Los Angeles. It was at UCLA, that Thomas met Ralph Kilmann, who joined the doctoral program.

Ken Thomas stayed at UCLA until 1977. He then went on to hold a series of academic appointments; Temple University (1977-81), University of Pittsburg (where Kilmann was then teaching) from 1981-6, and then the US Naval Postgraduate School. He retired from academic work in 2004.

Ralph Kilmann

Ralph Kilmann studied for his BS in Graphic Arts Management (graduated 1968) and his MS in Industrial Administration (1970) at Carnegie Mellon University. He then went to UCLA to study for a PhD in Behavioural Science. There, Kenneth Thomas was part of the faculty whilst himself working on a PhD.

Kilmann rapidly became interested in Thomas’ research into conflict and conflict modes. They shared a dissatisfaction with the methodology of Blake and Mouton’s version, though they liked the underlying styles and structure. Kilmann focused his studies on the methodologies for creating a robust assessment.

Publishing the Thomas Kilmann Conflict Mode Inventory

Together, they published their work in 1974. Partly by luck and partly good judgement, they chose not to include their 30-question assessment inventory in the academic paper they published. Instead, they took it to a publisher, who made it a widely-used tool. It is still published by the successor (by acquisition) of that original publisher.

Over the years, they have worked with their publisher to use the vast data sets now available to increase the reliability of the instrument, and extend its use to multiple cultures.

The questionnaire has 30 pairs of statements, of equal social desirability, from which you would select one that best represents what you would do. It takes around 15 minutes to complete. It is not a psychometric and requires no qualification to administer and interpret. So, it can be readily used to support training and coaching interventions around conflict with groups and individuals.

The Thomas Kilmann Conflict Mode Inventory

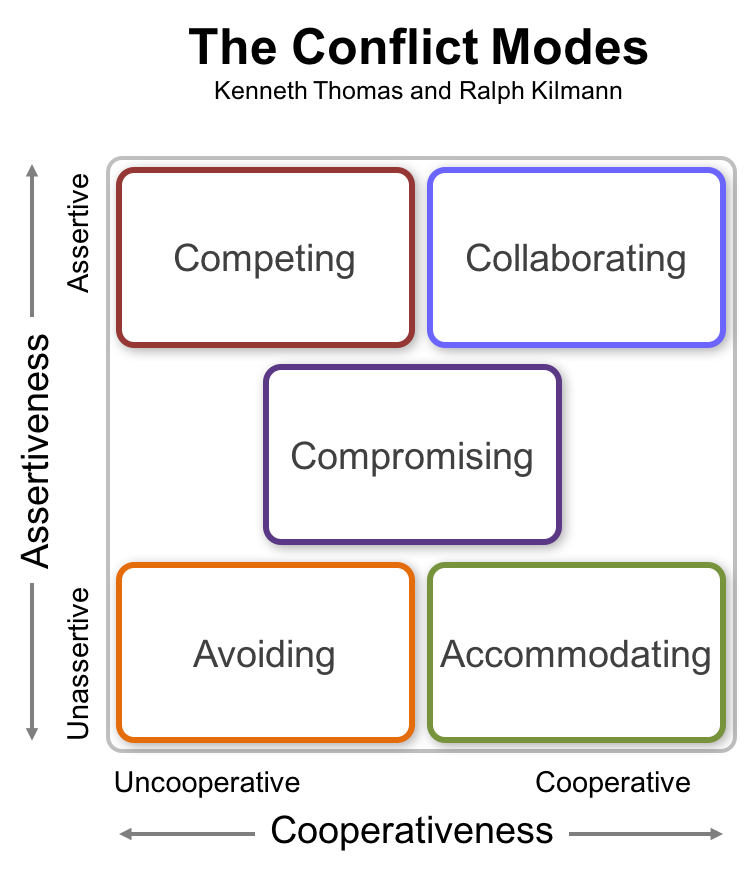

Kenneth Thomas and Ralph Kilmann are neither the first nor last to categorise your possible responses but, measured by popularity, they are by far the most successful. Like Jay Hall before them and Ron Kraybill later, their model looks at our responses on two axes.

The first axis is ‘Assertiveness’, or the extent to which we focus on our own agenda. The second is ‘Cooperation’, or our focus on our relationship with the other person.

The Five Conflict Modes

As with other models, there are five Thomas-Kilmann Conflict Modes.

Competing

A high degree of assertive behaviour, with little focus on the relationship, is referred to as Competing. In this mode, we seek to win above all else. It is a suitable style when success is vital, you know you are right, and there is a time pressure.

Accommodating

The opposite extreme is Accommodating. Highly cooperative and non-assertive behaviour is useful when you realise the other person is right, or when preserving the relationship or building emotional credit is foremost in your strategy.

Avoiding

When we want to invest little effort in the conflict, we use the Avoiding mode. With no effort deployed in either getting what we want or building a relationship, this is appropriate for trivial conflicts, or when we judge it is the wrong time to deal with the conflict. This may be due to hot tempers or a lack of sufficient preparation.

Compromising

The good old 50-50 solution is Compromising. When you and I give up equal portions of our objectives, neither gets what we want, but it seems fair. Likewise, whilst our relationship is not optimised, neither is it much harmed. Compromise suits a wide range of scenarios.

Collaborating

What can be better than compromise? When the matter is sufficiently important, it is worth putting in the time and effort to really get what you want … and build your relationship at the same time. This is the Collaborating mode, sometimes called “win-win”. Reserve it for when the outcomes justify the investment it takes.

Critique of the Thomas Kilmann Conflict Mode Inventory

The Thomas Kilmann Instrument has its critics. Many users find the forced choice questionnaire frustrating – sometimes wanting to select both options; sometimes neither. There are also concerns about applying the examples to users’ real-world contexts. Unlike the Kraybill tool it lacks distinction between normal and stress conditions.

Accepting these weaknesses, the model finds a range of useful applications, even beyond conflict; in team development, change management and negotiation, to name three. Above all, consider it because most users value the insights it gives them.

Just before Christmas, news came out that Google has updated the way its search engine works, so that it

Just before Christmas, news came out that Google has updated the way its search engine works, so that it  Google holds a huge amount of data about customer behaviour that could also be factored in. Let’s not forget that Google knows how often people search for your company name together with ‘complaints department’.

Google holds a huge amount of data about customer behaviour that could also be factored in. Let’s not forget that Google knows how often people search for your company name together with ‘complaints department’.