In last week’s Pocketblog, we took an overview of the Six Sigma approach to process improvement, and left readers with the statement: ‘it is time for the most interesting bit: the practical tools that non-experts can apply to making simple improvements from day to day.’

For all of the levels of certification that practitioners can acquire, most of us can simply understand and apply six sigma’s tools to day-to-day projects, problem-solving and improvements without training, just by understanding the basis and applying our own good sense and intuition. I am not arguing against the value of full training and certification, but it is a huge investment if all you want to do is fix a small issue.

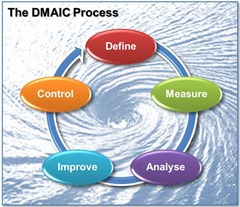

Indeed, many of Six Sigma’s tools have a life of their own outside the methodology and have simply been co-opted in to provide strength in depth for practitioners’ toolkits. Next week, we’ll do a round-up of some of these. This week, we’ll focus on the beating heart of the Six Sigma methodology, the DMAIC Process.

The Beating Heart: DMAIC

DMAIC can be viewed as a problem solving process, but I prefer to think of it as a ‘solution process’ because it starts with defining the solution you need to find.

DMAIC can be viewed as a problem solving process, but I prefer to think of it as a ‘solution process’ because it starts with defining the solution you need to find.

Let’s break it down:

.

.

.

Define

Define the solution you need, in terms of: who it affects (customers, clients, colleagues, stakeholders), the process involved, and the extent of the process (whether it is the full process or a part of the process). Choosing the right problem to solve is an important part of the Six Sigma process. It means making best use of necessarily limited resources. The Define stage ends with a team charter that sets out the scope and status of the project.

Measure

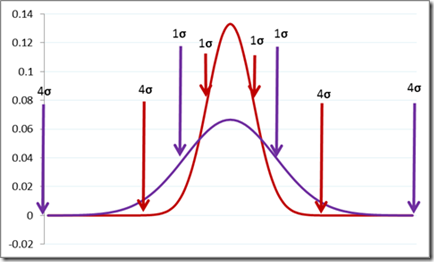

Six Sigma is nothing if not couched in mathematics and quantitative methods. This gives it its robustness. The second step in the DMAIC process is to measure the current performance level, to give a good baseline against which to evaluate improvement measures. This is a good opportunity to talk about Six Sigma’s Xs and Ys.

A Y is a measure of output performance. It is an effect of the process. Motorola talked of Big Ys as the things that matter most to the business’s most critical customers. The Measure stage of DMAIC concerns itself with Ys.

An X is is a cause – a factor, variable or process element which can affect the outcome. The Big Xs are the factor that have the greatest impact on Big Ys.

Analyse

Now it is time to find the cause of any failing in performance. At the Measure stage, we understood the performance (or Ys) – now we find what factors affect that performance (the Xs). Six Sigma has collated a host of quantitative and qualitative tools to gather data for the Measure stage and to interrogate it for the Analyse stage.

Improve

An effect Y is some function of one or more Xs so, in mathematical speak:

Y = f(X1, X2, X3, …)

If you can understand what Xs are important and how to change them to improve Y, then you can implement valuable changes. Having a strong philosophy of quantitative, evidence-based interventions, Six Sigma practitioners will always look for opportunities to conduct limited (low risk) trials to test the validity of their evaluation before a full implementation.

Control

The final step is about evaluating and sustaining the improvements. Practitioners will set up a regime to monitor and control the relevant X factors and monitor the resultant Ys.

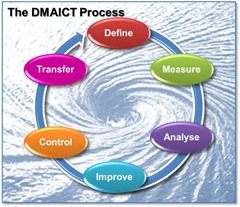

… and one more step?

In the UK, the Six Sigma Group (training and consultancy) advocates an extended DMAICT process that I would wholly endorse. Other organisations may, too. The final step is…

Transfer

Transfer what you have learned and the principles you have used to the operational staff who can then use this knowledge to maintain and further improve the processes. This is very much a step that is essential for external consultants to offer, if they want to avoid client-dependency. Of course, some consultants relish such a dependency, but transferring learning is more respectful, more sustainable and, ultimately I believe, more reputation-enhancing.

Learn More: References on the Web

The best website I have found, by far, is iSixSigma. It is a commercial site offering many related services, with free membership if you want additional information like newsletters. It has a lot of valuable articles and a Six Sigma dictionary.

MoreSteam.com is an online Six Sigma training business that also has a lot of freely accessible resources on its website. The link will take you to the Knowledge Center (US Site).

My third recommendation is DMAIC Tools – another site with a wide range of free resources to help you learn about aspects of Six Sigma. As its name suggests, this has a big focus on the tools and especially has a good coverage of the statistical side of the methodology.

Kahneman is perhaps the leading psychologist in the field of behavioural economics – very much a field du jour. His research was carried out with many collaborators including Paul Slovic, an expert in the field of perception of risk, and Richard Thaler, most notable for his use of the term “nudge” to describe how we can use perceptions to shift behaviour.

Kahneman is perhaps the leading psychologist in the field of behavioural economics – very much a field du jour. His research was carried out with many collaborators including Paul Slovic, an expert in the field of perception of risk, and Richard Thaler, most notable for his use of the term “nudge” to describe how we can use perceptions to shift behaviour.