Handle a complaint well and you will turn an unhappy customer into a wild fan of your business. Handle it badly and not only will they never return – they’ll tell their friends (10 to 15 of them according to The Handling Complaints Pocketbook).

When Range Rover’s new model was plagued with faults in the 1980s, Managing Director, Mike Hodgkinson, sent a simple message to every dealer. As soon as anyone comes in to complain, offer them the chance to drive a new car off the forecourt; there and then. In the year it took them to fix the problem, only one customer took them up on the offer. But the press went wild about their customer service commitment.

People know things go wrong with products. They know that services falter from time to time. They know you are human. So what they want is not perfection: they want to be listened to. By taking their complaint seriously, Range Rover signalled that customers were being listened to, so they were happy to let the company work on their problems.

Cost-Benefit Analysis

People will work hard to make your life hell if you fail to take their complaint seriously. How much does it cost to put something right? A bit of time, a bit of stock at cost price? Nowhere near the cost of dealing with an endless stream of calls, letters and visits. Add to that our increasing ability to publicise our frustrations and disappointments on the internet. Invest immediately in making things right. That way, you avoid the potential cost of the complaint and maybe win a new friend.

In fact, I would be tempted to aim to super-please: don’t just make things right, but make a generous gesture, that leaves people talking about that with their friends.

The Psychology of Customer Complaints? I’m OK

Sometimes customers do complain – and sometimes you will deserve it. What can you do when the mistake you made is minor, but the complaint is a big one?

One tool of basic business psychology points us to what may be going on – the customer thinks they are better than you are. In their mind, they are a good person, cruelly wronged. You, on the other hand, are stupid, malicious, or inadequate… in their mind.

Your customer is saying to themselves:

“I’m OK; you’re not OK”

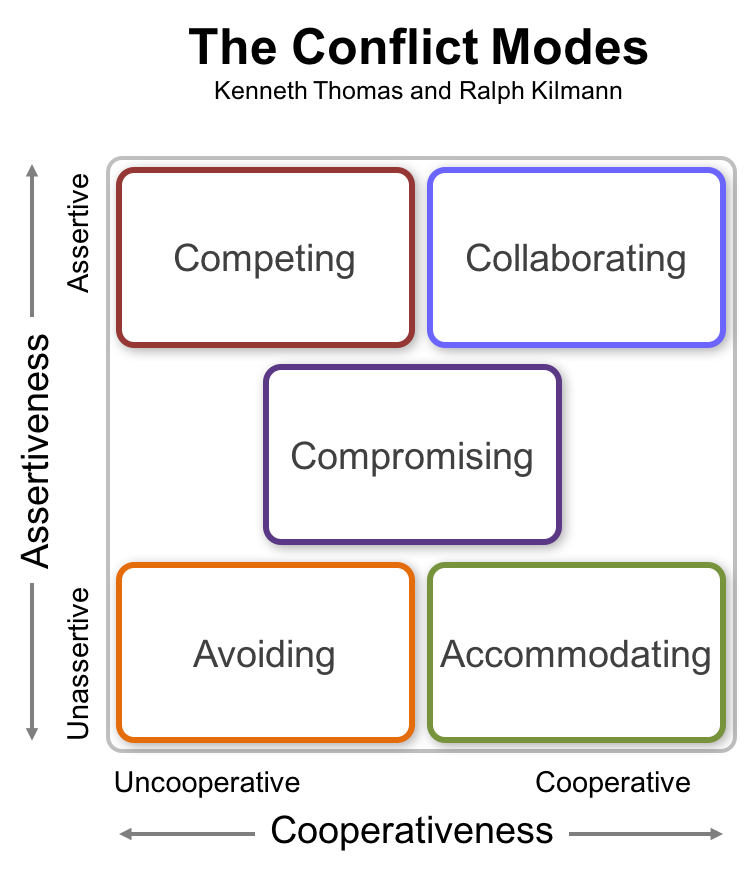

Why do some people turn a complaint into a conflict, and then fail to deal with that conflict effectively? That’s simple: they take the other tack and try to prove to the aggrieved customer that the customer is “Not OK”, and that they themselves are clearly “OK”.

This attempt to get one-up on the customer is doomed to fail. Would you go back to do business with someone who showed that attitude?

The secret to defusing the potential conflict is to show that you too are “OK”, by demonstrating that, like them, you recognise that the situation is unacceptable.

This means building rapport, by empathising with their point of view, then demonstrating that you want to solve the problem in a way that is intelligent, well-meaning and capable.

Two pocketbooks you may like: