Pocketblog is going back to basics. This is part of an extended course in management skills.

Time management is a vital part of your personal effectiveness. As a manager, you will face greater time challenges than you did as a team member; but you will also have additional resources and greater flexibility in how you use your time.

One of the simplest and most powerful time management approaches is John Adair’s Four-D System. This is documented in his (now out of print) Handbook of Management and Leadership.

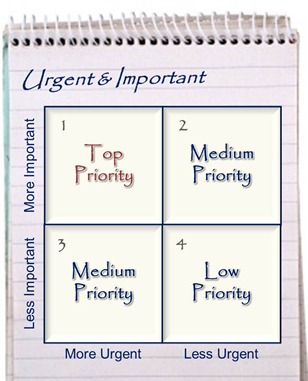

Adair starts with a standard Eisenhower Matrix putting urgency against importance.

Adair then identifies starting time management strategy for each class of activities:

- Do it now

- Delay it until you have some good quality time

- Do it quickly

- Drop it or Delegate it

Critique

As always, John has identified a powerful model with real practical application. Yet I can’t help feeling we must modify it a little. Here are three ways you can make it even more effective still:

Priorities

Although the urgency suggests that box 1 is top priority, this creates a high stress, low sustainability work style. Prioritise box 2 and you will find yourself planning and preparing ahead of urgency and so find less work falls into box 1.

Drop or delegate… Really?

If it is not worth your time to do it, why is it worth someone else’s time? Yes it may be important enough for someone else to do it, but don’t just Dump it on someone to avoid an assertive NO. Indeed, get in the habit of delegating Box 1, 2, and 3 tasks too, to develop the people who work for you.

More Ds…

We’ve already added Dump, but I don’t propose to honour it with emphasis. But Diminish is a powerful strategy. Look at the task and ask: ‘do I need to do all of it?’ If you can reduce the work required and still deliver all or most of the value, you will save valuable time. And there is another D: Decide. You need to decide which strategy to adopt. Unless, that is, you Defer your decision. If you do that as an example of purposive procrastination* it is a sound approach.

Exercise

Make an Eisenhower grid on a whiteboard or on the four panels of a door, or in your notebook. Use post-it type notes to jot down all the tasks facing you (big for the whiteboard/door or small for your notebook). Allocate the notes to one of the four quadrants. If everything is at the top left, re-calibrate your mental scales for importance and urgency.

*Purposive Procrastination: putting something off because there will be a better time to tackle it.