Pocketblog has gone back to basics. This is part of an extended management course.

Last week’s Pocket Correspondence Course module was about the three phases of creating change – or ‘transitions’, in Bridges’ language. This week, we need to address the question of how people respond to organisational change.

Have you ever noticed how people’s response to organisational change is sometimes out of proportion to the objective scale of the change itself? Organisational changes are hardly a matter of life and death, yet people often get scared, angry, upset or frustrated. These are powerful emotions that managers rarely feel ready to deal with.

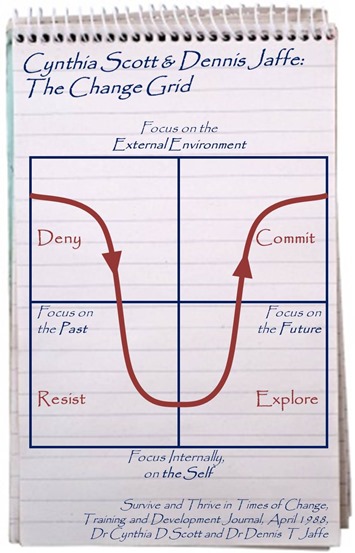

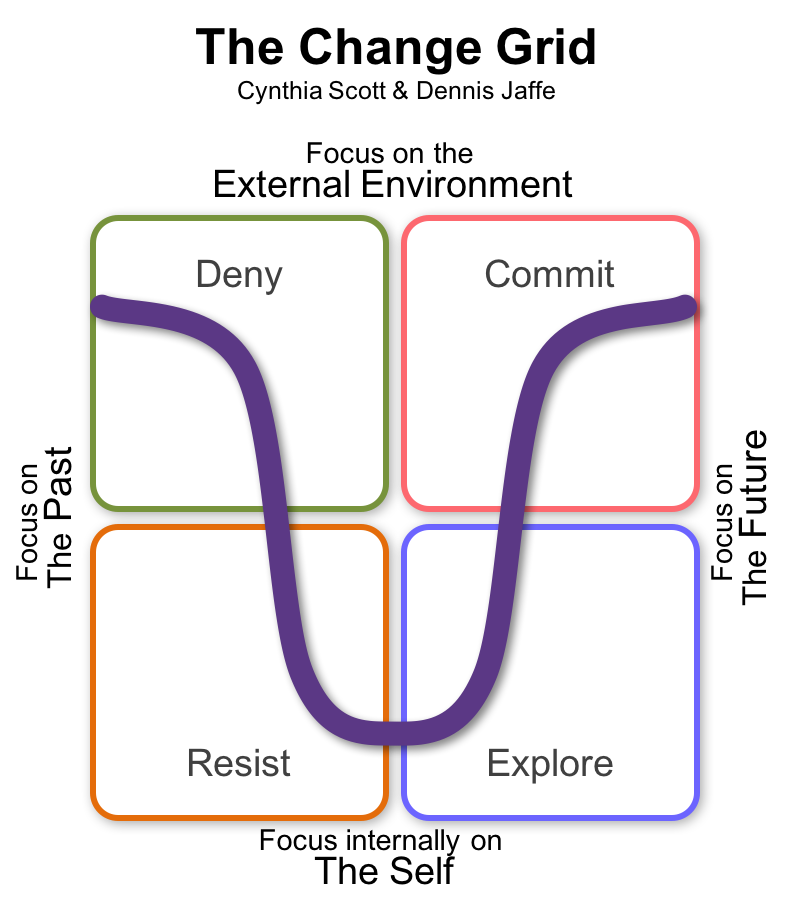

While many managers see organisational change as someone else’s specialism – the HR team, or the consultants, for example – it is your team. A general overview will help you understand some of the dynamics you encounter. One of the most useful and compelling models is that developed by Cynthia Scott & Dennis Jaffe.

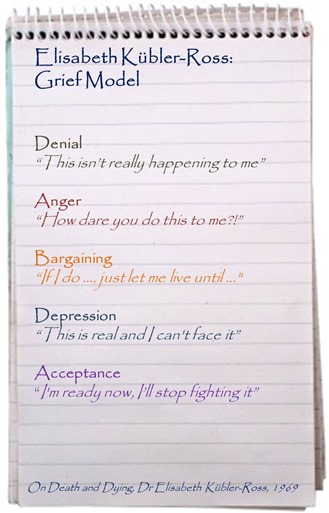

Grief: The work of Elisabeth Kübler-Ross

The Scott-Jaffe model owes much to the work of Dr Elisabeth Kübler-Ross. She researched the way people deal with tragedy, bereavement and grief, that led her to the development of a widely used description of grief as following five stages: denial, anger, bargaining, depression and acceptance – often remembered with the acronym DABDA.

The responses that Dr Kübler-Ross described served your ancient ancestors well. They did not emerge in an environment of shifting organisational structures and operational processes: the changes they encountered were often life threatening.

In modern times, we must use the same underlying physiology and brain chemistry to cope with both emotional trauma and an office move. It seems unsurprising, therefore, that when Scott and Jaffe researched responses to organisational change, they found a similar pattern.

Scott and Jaffe’s Four Stage Response to Change

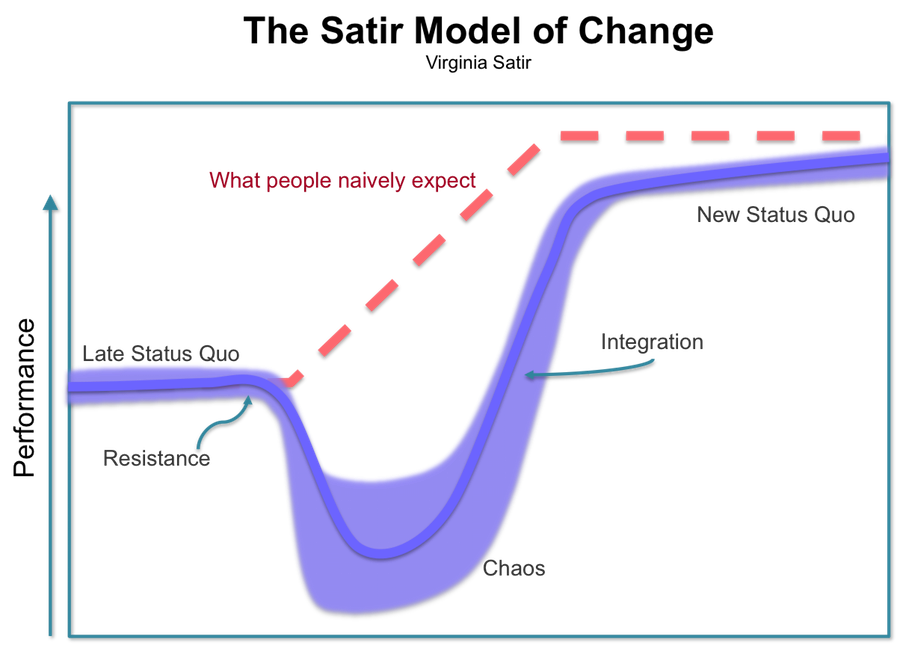

Scott and Jaffe’s model suggests that we move through four stages as we respond to organisational change. Clearly, if we quickly perceive the change as beneficial, we will jump from the first to the fourth.

Denial

Initially, the meaning of the change fails to sink in: we are happy enough (or at least comfortable) with the status quo, so our minds reject the reality of change. We act as if nothing has happened and Scott and Jaffe called this stage Denial.

Resistance

Once we start to recognise the reality of change, we start to Resist it. This arises from our aversion to loss – we focus on the elements of the status quo we will need to give up and our brains assign that a far greater weight of attention and value than any potential gains.

We do this first at the emotional level, showing anger, anxiety, bitterness or fear, for example, and later by opposing the change actively, engaging our critical faculties to find reasons to resist. Organisations see increases in absence, complaints and losses, and drops in efficiency, morale and quality.

Exploration

When managers like you face up to the resistance and engage with it in a respectful and positive way, people can start to focus on the future again. They will Explore the implications of the change for them and for their part in your organisation. They will look for ways to move forward. This can be a chaotic time, but also an exhilarating one – particularly when the benefits of the change are significant.

Commitment

Eventually people start to turn their attention outward as they Commit to the new future.

Other Models of Change

Scott and Jaffe are not the only researchers to articulate a model of organisational change. There are other, similar, models. Perhaps the best known of the three-phase models is Kurt Lewin’s ‘Freeze Phases’ that we covered in the previous Management Pocketblog: Unfreezing – Changing – Refreezing. We also saw William Bridges’ three-phase ‘Transitions’ model: Letting go – Neutral zone – New beginnings.

These are all powerful as predictive models of change and, like all models, none is true. Yet each offers up valuable insights which can help you predict, understand and mange change.

- The Managing Change Pocketbook

- The Handling Resistance Pocketbook

- Survive and Thrive in Times of Change,

Training and Development Journal, April 1988,

Dr Cynthia D Scott and Dr Dennis T Jaffe

This article is not available freely on the web. - On Death and Dying,

Dr Elisabeth Kübler-Ross, 1969