Pocketblog has gone back to basics. This is part of an extended management course.

- How do you gather the knowledge that you need, to do your job?

- Who do you go to for wise advice?

- When you find them, how do you access their opinions?

Do you get it?

Of course you do: questioning is the way we explore our world, the way we discover new ideas, understand problems, and find solutions. Questions are how we raise awareness in ourselves and others, how we help people to learn and how we get the answers we need.

So one could argue that management is all about questions and answers. That would be easy. It is far harder to determine which is more central to your role as manager: are you there to ask the right questions, or to find the good answers? (please debate that question in the comments section)

We often think questioning is easy, but there is a skill to it, which consists of three essential disciplines:

- Spotting what to question

- Structuring your questioning process

- Asking your questions artfully

What to Question

Listening to people can give you all of the clues you need about what to question. Here are five examples of the most questionable types of statement:

- Adverse outcomes beg questions about causes, and assumptions about causes beg questions that seek evidence to justify or falsify them.

- Interpretations of events beg the question of what evidence supports that interpretation.

- When someone is struggling to master a new skill or technique, asking the right question can direct their attention to the most important insight.

- Generalised and prejudicial assertions beg the question not just of how you know that they are true, but of whether they do indeed stand up to objective evaluation.

- When you are asked for a solution, questions will help you to understand the problem better.

The fallacy of petitio principii, or ‘begging the question’, arises when a proposition which requires a proof is assumed to be true without that proof.

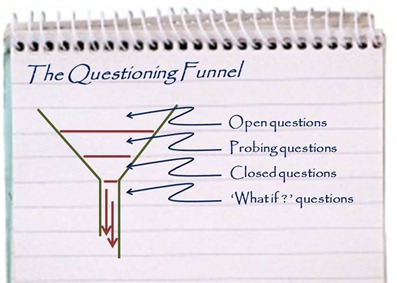

The Questioning Process

Learning more from a person – or even a scientific enquiry of nature – follows a clear process:

- Big, open questions to get a survey of the relevant information.

- Probing questions that explore more detail about the particular areas of interest

- Closed questions to test understanding and confirm facts

- What if? questions to test how the answers stand up to experimentation and related scenarios

Artful Questioning

One question has more power than any other. It is the one that small children ask repeatedly and the extent of the frustration it generates in their carers underlines its potency:

Why?

The question ‘why’ probes deeply, looking for causes, reasons and purpose. As a scientific enquiry into nature, or as a diagnostic probe into events, it is hugely effective, as underlined by the ‘Five Whys’ process within Six Sigma.

But things are different when you ask a person why they did something. You will usually get a defensive answer. ‘Why?’ feels like an attack on the values that direct our decision making, so we react against the question and rarely give a resourceful answer. A better question might be: ‘what were your criteria when you chose to do that?’

How else can you ask the question ‘why?’

without using the word ‘why’?