Pocketblog has gone back to basics. This is part of an extended management course.

We are working through a series of blogs, looking at some of the essential models that a project manager will need. We are covering:

- The Project Lifecycle

- The Triple Constraint

- Stakeholder Management

- The Critical Path (here), and in future blogs

- The Gantt Chart

- Risk Management

One of the pieces of project jargon that causes most confusion is ‘Critical Path’ and ‘Critical Path Analysis’, the process of calculating the critical path. The concept is actually quite simple, providing you start at the beginning.

Tasks, Duration and Sequence

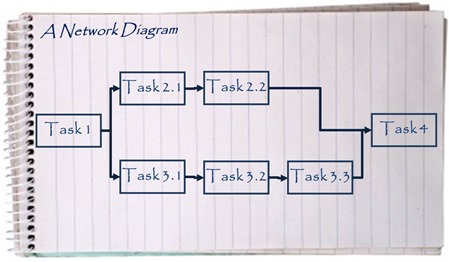

The first step in preparing a project plan is to identify all of the tasks you will need to complete. When you have done this, for each task, you must estimate how long it will take. The third key step is to figure out how the tasks connect up, logically, into a sequence. For most of them, one task will be followed by another, which will be followed by another. In project management jargon, this is a series of ’finish-to-start dependencies’. This sequence creates what is known as a ‘work stream’. The complications arise when some tasks can run in parallel to one-another, when some tasks can trigger the start of more than one task, and when some tasks can only start when more than one task has finished. There are more complications than this, but that’s enough and covers most small to medium sized projects! The best way to make sense of all of this is to draw yourself a flow chart; what is known as a ‘network diagram’.

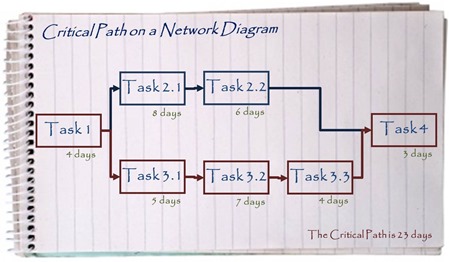

Calculate the Critical Path

Once you have the logic of your network drawn out, you can add your estimates of the duration of each task. These will allow you to calculate how long each path through the network will take. The longest path is called the ‘Critical Path’. It is critical because any delay (or ‘slippage’) to a task on that path will cause a delay in the completion of your project.  There you have it – simple in concept. Of course, like much that is simple, in the real world it is seldom easy. Calculating (and optimising) the critical path for a large, complex project with very many interdependent tasks is a big computation. When the methodology was invented in the 1950s, it was a big job to undertake. Nowadays, all but the very the biggest projects can be planned, optimised and monitored with the help of software running on a standard personal computer. I will never forget having the chance to look through the network diagram of the project to build and launch the first NASA Space Shuttle. Hundreds of pages of large paper and small print. ‘But’ said the project manager who showed me it, ‘when they planned the Mercury and Gemini missions in the 1950s, every time an engineer or project manager wanted to change the logical sequence, the network (or a chunk of it) had to be re-drawn by hand.’ How would that affect our attitude to getting it right the first time?

There you have it – simple in concept. Of course, like much that is simple, in the real world it is seldom easy. Calculating (and optimising) the critical path for a large, complex project with very many interdependent tasks is a big computation. When the methodology was invented in the 1950s, it was a big job to undertake. Nowadays, all but the very the biggest projects can be planned, optimised and monitored with the help of software running on a standard personal computer. I will never forget having the chance to look through the network diagram of the project to build and launch the first NASA Space Shuttle. Hundreds of pages of large paper and small print. ‘But’ said the project manager who showed me it, ‘when they planned the Mercury and Gemini missions in the 1950s, every time an engineer or project manager wanted to change the logical sequence, the network (or a chunk of it) had to be re-drawn by hand.’ How would that affect our attitude to getting it right the first time?

From the Management Pocketbooks series:

From the Management Pocketbooks series: