Pocketblog has gone back to basics. This is part of an extended management course.

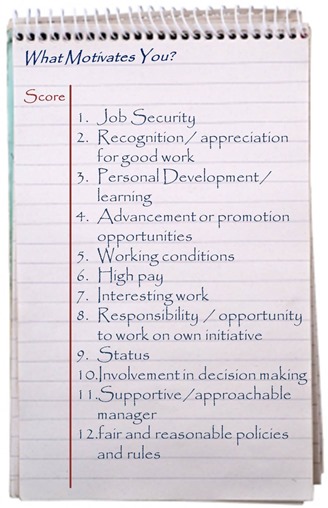

Exercise 1: What Motivates You?

This is a list of factors that commonly motivate people at work. Score the factors from 12 to 1, with 12 being the most important and 1 the least important, according to your perceptions of what motivates you.

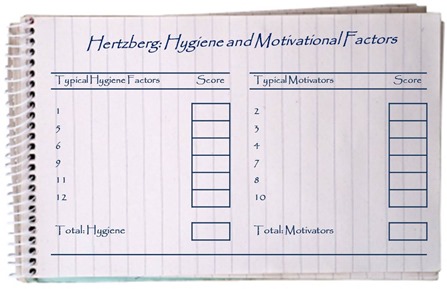

Herzberg’s Hygiene and Motivational Factors

Traditionally, motivation was viewed as single scale from low to high. Frederick Herzberg’s research led him to propose that dissatisfaction and satisfaction were not opposites of each other, but that we have two scales:

- From strong dissatisfaction to no dissatisfaction

Some things leave us upset or angry. Take them away and we don’t feel good – we just stop being dissatisfied.

Herzberg called these ‘Hygiene Factors’. - From no satisfaction to strong satisfaction

Some things don’t bother us if they are missing, but we are really pleased by their presence and motivated to achieve them.

Herzberg called these ‘Motivational Factors’.

This nicely explains why a messy workplace kitchen or rest-room gets people massively annoyed, but nobody celebrates the fact that their warehouse has clean facilities – this is quite literally a hygiene factor.

If hygiene factors are not right, they dominate workplace agenda, causing poor morale and motivation. Putting them right will not make a great workplace but it will stop the rot.

Few people will be motivated by motivation factors until hygiene factors are right. But once they are, use motivating factors to boost morale.

Note that some people have different attitudes. To some, money is a hygiene factor, for others it is a motivator. What is nearly always true is that my perception of a fair wage determines the point at which money for me moves from being a hygiene factor (below that level) to a motivational factor (above). However, my attitude to money and what it could bring me will determine the extent to which it really motivates me.

The Results

Hertzberg gave examples of hygiene and motivating factors and there were six of each in the list you looked at. Tot up your scores for each by entering the scores from the top of the article into these boxes. If you score highly on hygiene factors, this suggests things aren’t quite right at work for you. If you score highest on motivational factors, then let your bosses know what they need to do for you.