Linda Hill’s 2011 book, Being the Boss, was rated as one of Wall Street Journal’s 5 books to read in 2011, to build your career. But that work has since been eclipsed by the work Hill has done in collaboration with three colleagues. In this, she looks at how leaders spur innovation. The secret, she finds, is in ‘collective genius’.

Very Short Biography

Linda Hill was born in 1957, and attended Bryn Mawr College, where she earned a BA in Psychology. She then went to University of Chicago, to read for her MA in Educational Psychology, which she followed with a PhD in Behavioural Science.

In 1984, Hill joined the staff of the Harvard Business School, as an assistant professor. She became an associate professor in 1991, and full professor in 1995. Since 1997, she has been Wallace Brett Donham Professor of Business Administration at the Harvard Business School, where she has studied a broad spectrum of management and leadership topics. Her current interests remain centred on leadership, with particular focus on innovation, leading in the 21st century, and the new black business elite of South Africa.

Linda Hill’s Ideas

Becoming a Manager

Hill’s first book was Becoming a Manager (2003). This is a robust guide to taking on a management role, with a strong focus on its challenges within a career context. There is little innovative in it, but it does form a good guide to an important (and under-studied) career point. Hill concludes that a new manager must learn to:

- Set the strategy and direction for their team

- Align their people around that direction

- Motivate and inspire them to achieve their goals

Being the Boss

Being the Boss (2011) is an altogether more substantial contribution, co-written with Kent Lineback. In this, Hill suggest three priorities for leaders:

- Managing yourself

- Managing your network

- Managing your team

So far, so standard. What makes this book stand out is its depth,and the way it gives genuinely valuable pointers to help managers and leaders progress on their journey. It is both thoughtful and practical. This is a book that is filled with pragmatic advice, and has inspired a mandatory module in Harvard’s MBA programme.

Collective Genius

It is Hill’s 2014 book, co-written with three other researchers, that has brought her to prominence as one of the foremost contemporary management thinkers. Collective Genius: The Art and Practice of Leading Innovation sets out to explore how leaders can create an innovative culture.

The research, conducted through a series of interviewers with leaders at highly creative organisations, concludes that the traditional image of a visionary leader driving creativity is a false one. Visionaries rarely lead great innovation. Instead, they tend to be the ones who get in its way.

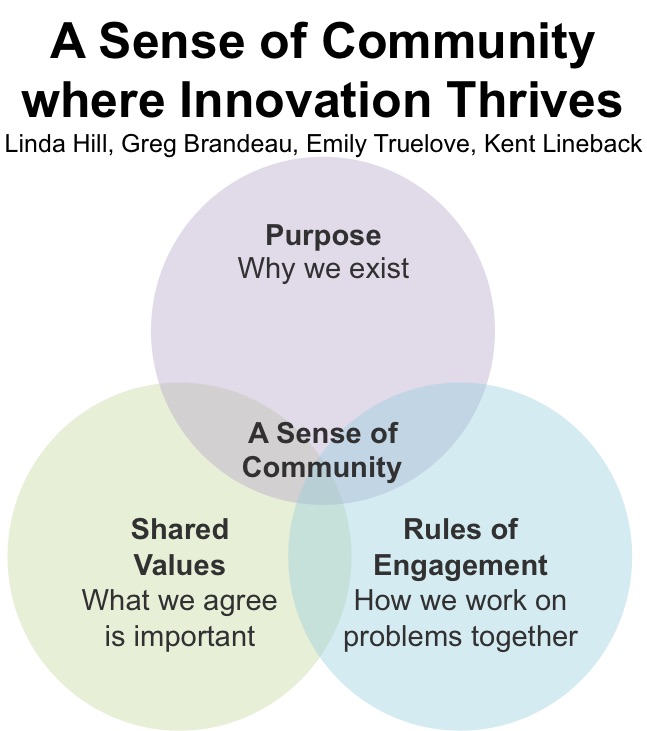

A constant stream of good innovation needs leaders who are ‘social architects’ that can create a culture of collaboration. This means creating a sense of community, that rests on shared values, a clear purpose, and mutually agreed ways of working together. The diagram below illustrates this and is adapted from the book.

Once the leader has created this shared culture of collaboration, they need to give the groups a chance to discuss, argue, test, experiment and learn from their successes and failures. Crucially, the leader also needs to give ideas long enough to develop, so that evaluation is based on real results, rather than anticipation. In low creativity cultures, leaders select from competing ideas too soon. They reject and lose good ideas that do not seem as likely to thrive, while in their early stages.

Where different ideas are allowed to develop and be tested fully in parallel, decision-making is more robust. The authors identify three leadership abilities, which the leader must also develop within the group:

1. Creative Abrasion

Creating a culture of robust debate and challenge, that will generate the new ideas.

2. Creative Agility

A rapid cycle of test, learn, adjust that values experimentation as the way to optimise.

3. Creative Resolution

A decision-making approach that shuns ‘either-or’ thinking in favour of integrating different and sometimes opposing ideas.

In a fast-moving and complex world, easy solutions will be few and far between. We need a constant supply of new insights into how we can better synthesise subtle and complex solutions, and make wise choices about which to invest in. Many reviewers suggest that every CEO should be reading this book. I just wish it could find its way onto the reading pile of some more senior politicians.

Management Pocketbooks on related topics:

How to Manage for Collective Creativity

Linda Hill speaking at TEDx in 2014.