If you are looking for one simple model that can more than pull its weight in understanding management, then look no further. Robert Blake and Jane Mouton developed their Managerial Grid in the 1950s and early 1960s. Its simplicity captures vital truths about management styles and their implications.

Every manager should understand the basics of the Managerial Grid. Even if you are not familiar with it, there’s a good chance you will recognise its organising principle. And if you don’t, then read on. This is fundamental stuff.

Robert R Blake

Robert Blake was born in Massachusetts, in 1918. He received a BA in psychology and philosophy from Berea College in 1940, followed by an MA in psychology from the University of Virginia in 1941. His studies were broken by the war, where he served in the US Army. On his return, he completed his PhD in psychology at the University of Texas at Austin in 1947.

He stayed at the University of Texas as a tenured professor until 1964, also lecturing at Harvard, Oxford, and Cambridge Universities. In the early 1950s, he began his association with his student, Jane Mouton, which led to their work together at Exxon, the development of the Managerial Grid, and co-founding of Scientific Methods, Inc in 1964. The company is now called Grid International.

Robert Blake died in Austin, Texas, in 2004.

Jane S Mouton

Jane Mouton was born in Texas, in 1930. She got a BSC in Mathematical Education in 1950, and an MSc from Florida State University in 1951. She then returned to the University of Texas, completing her PhD in 1957. She remained there until 1964 in research and teaching roles.

It was at the University of Texas that she met Robert Blake. They were hired by Exxon to study management processes after Blake collaborated with Exxon employee, Herbert Shepard. The work led to their development of the Managerial Grid and, in 1961, to the founding of Scientific Methods, Inc (now Grid international).

Jane Mouton died in 1987.

The Managerial Grid

In many ways, Blake and Mouton’s Managerial Grid is a development of the Theory X, Theory Y work of Douglas McGregor. The two researchers were humanists, who wanted to represent the benefits of Theory Y management.

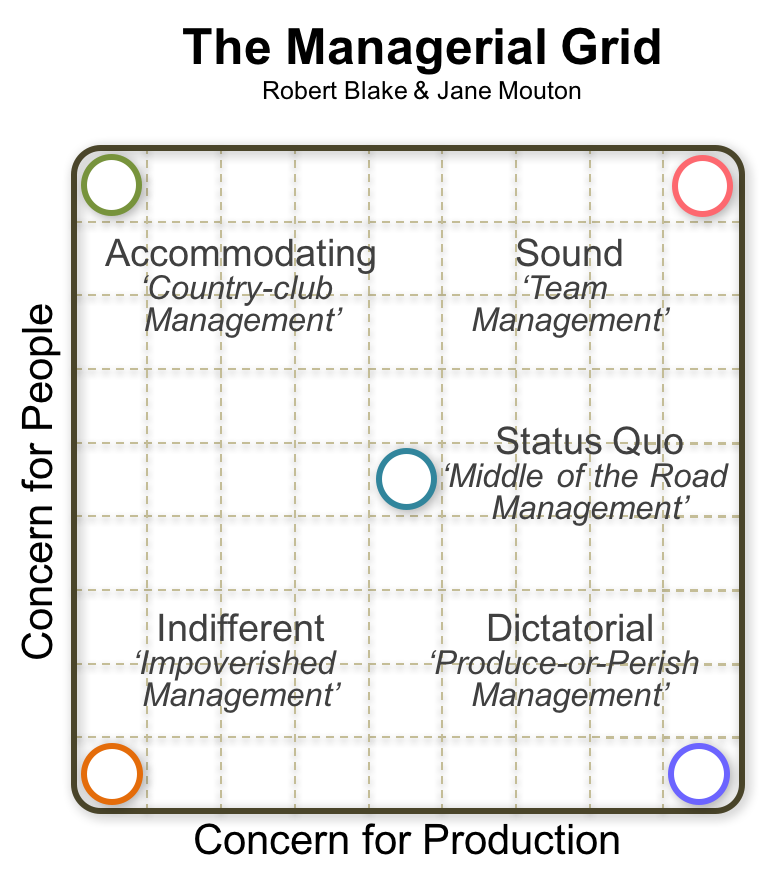

They did so by defining two primary concerns for a manager:

- Concern for People

- Concern for Production

(sometimes referred to as Concern for Task)

Although their work is often simplified to a familiar 2 x 2 matrix formulation, it was a little more subtle. They created two axes and divided each into nine levels, to give a 9 x 9 grid. It was the extreme corners, and the centre, of this grid that they labelled and characterised. They recognised that most managerial behaviours fall within the grid, rather than at the extremes.

The Five Styles on the Grid

The five styles they originally identified are at the corners and in the centre. They are still best known by the first labels Blake and Mouton published for them (shown in italics in our illustration). Blake did later refine those labels, as well as define two additional styles. This was after Jane Mouton died, in 1987.

Indifferent

Impoverished Management | Low Results/Low People

This is an ineffective management style, in which an indifferent manager largely avoids engaging with their people or the needs of the job at hand. Such managers reason (wrongly) that if you don’t do much, little can go wrong, and you won’t get blamed. The Peter Principle suggests managers rise to their level of incompetence, and here is the style we may see as a result.

This style is only suitable as a calculated decision to be hands off and delegate to a highly capable and strongly motivated team. Even then, a retreat into the very corner is not appropriate.

Dictatorial

Produce-or-Perish Management | High Results/Low People

Authoritarian managers want to control and dominate their team – possibly for personal reasons, or an unhealthy psychological need. They don’t care about their people, they just want the results of their endeavours. Away from the extreme, this Theory X-like approach can be suitable, in a crisis.

The theory X origin of this behaviour mean managers here prefer to enforce rules, policies and procedures, and can view coercion, reprimands, threats and punishment as effective ways to motivate their team. Short term results can be impressive, but this is not a sustainable management style. Team morale falls rapidly and compromises medium and long-term performance.

Status Quo

Middle-of-the-Road Management | Medium Results/Medium People

This is a compromise and, like all compromises, it is characterised as much by what the manager gives up as by what they put in. A little attention to task and a bit of concern for people sounds like balance, but it also reflects a level of impoverishment – not much concern for either.

This is neither an inspiring, nor developmental approach to management and can only be effective where the team itself can meet the leadership deficits it leaves behind. A good manager could only legitimately use this approach where this one team is a low priority among other competing demands, and the manager is confident they can manage themselves to a large degree. If not, mediocrity will be the best result the manager will achieve from this strategy.

Accommodating

Country Club Management | High People/Low Results

Sometimes, you need to rest your team, take your foot off the accelerator, and accommodate their needs. These may be for a break, for team-building, or for development, perhaps.

However, as a long term strategy, it is indulgent, and leads to complacency and laziness among team members. There is little to drive them, yet we know pride in achievement, autonomy, and development are principle workplace motivators. Without a sufficient focus on production, the team will get little of any of these.

The work environment may be relaxed, fun, and harmonious, but it won’t be productive,. The end point will also be a lack of respect, among team members, for the manager’s leadership.

Sound

Team Management | High Production/High People

According to Blake and Mouton, the Team Management style is the most effective approach. This is routed in McGregor’s Theory Y. It is the most solid leadership style, with a balance of strong concern for both the means and the end.

A manager using this style will encourage commitment, contribution, responsibility, and personal and team development. This builds a long-term sustainable and resilient team.

Peaks and troughs in workload and team needs will mean a flexible manager with stray away from the corner from time to time, either towards accommodating or dictatorial styles. But this flexibility and their general concern for both dimensions will prevent them from an unhealthy move right into the corners.

When people are committed to both their organisation and a good leader, their personal needs and production needs overlap. This creates an environment of trust, respect, and pride in the work. The result is excellent motivation and results, where employees feel a constructive part of the company.

Two Additional Styles

After Mouton’s death, Blake continued to refine the model, adding two additional styles.

Opportunistic Management

Some managers are highly opportunistic, and are prepared to exploit any situation, and manipulate their people to do so. This style does not have a fixed location on the grid. Managers adopt whichever behaviour offers the greatest personal benefit. It is the ultimate in flexibility, and is highly effective.

What matters is motivation. Some managers are highly flexible for reasons of great integrity others for purely self-serving reasons.

Paternalistic Management

The loaded label represents a flip-flopping between accommodating ‘Country Club management’ and dictatorial ‘Produce-or-Perish management’. At each extreme, this managerial style is prescriptive about what the team needs and how they will supply it.

The subtlety of sound team management adapting to the team’s needs is not present. Such managers rarely welcome a team trying to exercise its own autonomy. They will feel it as an unwelcome challenge.