This is part of an extended management course. You can dip into it, or follow the course from the start. If you do that, you may want a course notebook, for the exercises and any notes you want to make.

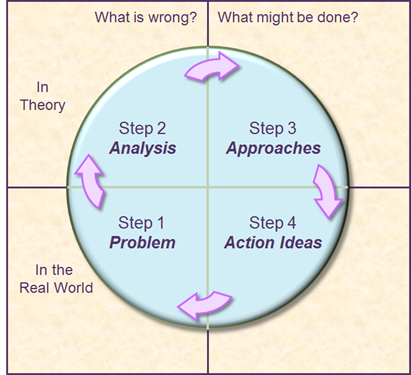

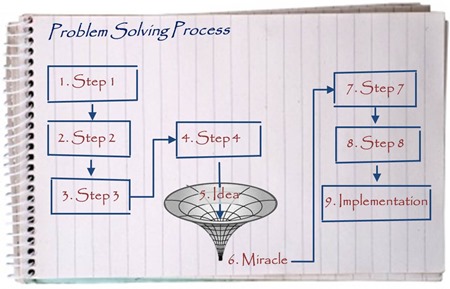

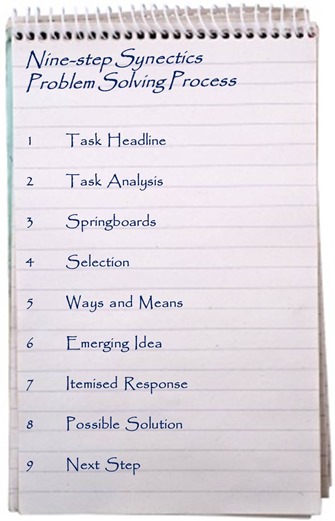

In last week’s Pocket Correspondence Course module, we looked at problem solving, using the Synectics process. The problem with all problem solving processes is the black hole in the middle:

That black hole is where a brilliant, innovative, creative idea happens.

Many, Many Approaches to Creativity

There are many approaches to stimulating this sort of creative idea, from bisociation to nyaka, from the Eureka method to Merlin. You will find all of these and more in The Creative Manager’s Pocketbook.

But there are two ‘master techniques’ that will serve a busy manager magnificently well. Let’s try them out. To do so, think of one or two problems for which you want to find a creative solution. Write them down in your notebook in the form:

‘I would like to discover how to…’

This is your ‘problem definition’.

Exercise 1: Sleep on it

Most creativity methods implicitly recognise that creativity happens while we are not looking. Given a problem, our brains will work on it at any time they have spare capacity. So the master technique creates that space by taking your mind off actively considering the problem – or anything else. Go for a walk, go out with friends or, better yet, take a nap. Best of all, write down your problem definition before you go to sleep at night.

The second stage to the process recognises that, when our brains are busy, ideas can’t find the room to get out. They tend to emerge either when something in our environment triggers them to emerge, because it bears some form of similarity, so the barrier is lowered, or in the spaces when our minds are still, like in the shower, walking to the bus stop, or drinking a coffee.

Since you cannot arrange the trigger event that lowers the barriers momentarily, create the quietening conditions that will let your idea emerge. Spend some time doing nothing that requires deliberate thought. Daydream, jot random thoughts onto a page, or sip a coffee or a tea, looking out of the window.

Constructive idleness is one of the two master techniques for creativity.

Exercise 2: Up and Down

Many creativity techniques are about breaking the mental constraints that we impose on our own thinking and finding a new way to look at the problem: so called ‘thinking outside the box’. Here, ‘the box’ represents your mental constraints.

The master technique for doing this is to start with your problem definition: ‘how to…’ and ask your self:

‘What is my reason for wanting to…?’

Keep asking this question of each answer (akin to the 5 Whys Technique) until the answer is both fundamental and self-evidently true. This is your ultimate purpose. Having gone ‘up’, now come back down, with the question:

‘How else can I achieve this purpose?’

Keep asking this to generate creative new options.

For general negotiating skills, I am yet to be persuaded that any book has overtaken ‘

For general negotiating skills, I am yet to be persuaded that any book has overtaken ‘