Fortune Magazine named him the greatest manager of the Twentieth Century. He took a well-managed and moderately successful corporation and grew it for 100 successive quarters, transforming it in the process. And now he spends his time teaching younger managers to do the same.

Short Biography

John Francis Welch Jr was born in 1935 and grew up in Massachusetts. He gained a BSC in Chemistry from the University of Massachusetts in 1957 and went on to post-graduate study at the University of Illinois, where he earned an MSc and then a PhD in Chemical Engineering. From there, he joined General Electric, in 1960.

After concerns about the bureaucracy in his first year, a manager persuaded him to stay and from then, his rise through the organisation was steady and fast. He was their youngest General Manager ever, in 1968 and became a divisional vice president in 1972. In 1979, he was a Vice Chairman and Executive Officer, and a year later was named as the next Chairman and CEO of General Electric. He took the post in the autumn of 1981. He set his sights on creating the world’s most valuable company.

He spent the next twenty years growing GE spectacularly, in two phases that we can crudely characterise as ripping down the old (1980s) and building the new (1990s). As soon as he took over, he saw that changes in world business and the then emergent growth of Japanese business would mean that the well-managed but moderate-performing GE would flounder unless he could successfully change it, to compete.

His changes were a great success, growing share price from $4 in 1981 to $133 in 1999, with profits rising from $1.6 billion to $10.7 billion when he left the company in 2001. His retirement has seen the publication of three hugely successful books (co-written with his third wife, journalist Suzy Welch) and the creation of his own business school, the Jack Welch Management Institute, which teaches MBA programmes under the aegis of the private Strayer University.

Welch’s books are:

- Jack: Straight from the Gut (2003) – his biography, co-written with John Byrne. Reportedly earned him a $7million advance.

- Winning (2007) – his perspective on how he succeeded at GE – along with its companion volume…

- Winning: The Answers (2007) – both co-written with Suzy Welch

- The Real-Life MBA (2015) – a guide to management and business inspired by his teaching – also co-written with Suzy Welch

Ripping Down the Old – How Welch Disrupted GE in the 1980s

- Welch started with a big investment in GE’s corporate management training facility, Crotonville in New York State.

- He shifted the focus of GE’s business towards services, creating around 6,000 new businesses during his tenure

- He determined to deal with unprofitable businesses, famously saying that if a business was not rated at number 1 or 2 globally, it would be fixed, closed, or sold. This is a pretty rigorous application of the strategy implied by the BCG Matrix.

- He flattened the management structures and devolved power down to business units, creating far more decision-making autonomy for general managers.

- His closures and simplifying activities resulted in a massive ‘downsizing’ of the business by nearly 200,000 staff, saving the business $6 billion and earning him the epithet of ‘Neutron Jack’ (after the Neutron Bomb that kills people while leaving infrastructure standing).

Building the New – How Welch Re-built GE in the 1990s

Having torn down what Welch perceived as not working, in the 1990s, he turned to creating a set of sustainable practices.

- Managers were evaluated against the ‘Welch Matrix’ of values and new managerial appointments and deployments took up a full month of his time every year. He articulated his 4 Es of ‘energy, energisers, edge, and execution’, and placed adherence to values above achievement of figures.

- He asked experts at Crotonville to develop a mechanism to hold middle managers at all levels accountable and in 1988 launched the ‘Work Out’ process of town hall meetings where managers had to give answers and make decisions, and created opportunities for large group brainstorming. This process was widely emulated by other businesses.

- He learned how Walmart – then as now, hugely successful – stayed at the top of its game by gathering information constantly about what promotional activities are working and failing (for their competitors as well as for themselves) and then rapidly making changes. He adapted what he learned into GE’s QMI process of ‘Quick Market Intelligence’. This opened up huge commercial opportunities.

- To encourage innovation, he recognised the need for excellent communication up and down the organisation, and across its businesses and divisions. His ‘Boundaryless Organisation’ was, perhaps, one of the biggest drivers of GE’s success.

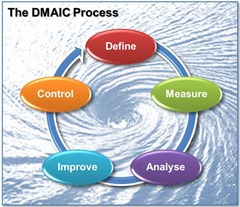

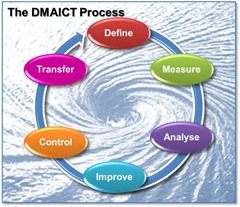

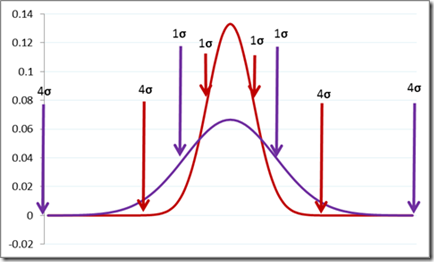

- In 1997, Welch initiated rigorous quality management, mandating Toyota’s ‘Six Sigma’ process throughout the business, expecting huge numbers of managers to be trained and gain their ‘belts’.

- Finally (for this quick summary), Welch spotted the coming of the web as a primary means of doing business. Throughout the mid to late 90s, GE businesses were adjusting and developing their practices in a piecemeal fashion. In 1999 Welch launched his ‘destroyyourbusiness.com’ initiative to compel every part of GE to reinvent itself.

The upshot of all of this was not just spectacular growth, which other great CEOs have achieved. Welch was able to create a lasting change that persisted under the next CEO.

Pithy Soundbites

Welch is well known for coining pithy soundbites. Here are a few favourites.

- ‘Change before you have to’

- ‘Lead rather than manage’

- ‘Control your destiny or someone else will’ (also the title of a 1995 book about how Welch was making his changes).

- GE is ‘the largest petri dish of business innovation in the world’

- ‘For a large organisation to be effective, it must be simple’